NEW YORK’S RICH GET CREATIVE TO FLEE STATE TAXES. AUDITORS ARE ON TO THEM

(Bloomberg) -- At New Jersey’s Teterboro and Long Island’s Islip airports, dozens of private jets destined for Florida take off at times such as 11:42 p.m. or 11:54 p.m.

Over at JFK, a regular flight from San Juan, Puerto Rico, arrives at a seemingly purposeful time: about 15 minutes after midnight.

Meanwhile, tax attorneys tell stories of clients idling in their luxury SUVs near the New Jersey entrance to the George Washington Bridge shortly before 12 a.m., waiting for the clock to turn before crossing the state line to New York.

When it comes to taxes and the wealthy, every minute matters — especially for those who have left New York and declared residency elsewhere. At a time more high earners are departing, or at least are claiming to, state officials are stepping up already-intense scrutiny to make sure former residents have actually moved. It’s a complex operation that involves cutting-edge artificial intelligence and tracking everything from travel to the location of people’s pets.

For the ultrarich, even just an extra day in the wrong place could mean millions in income-tax liability.

“The minute you file a partial return you’re going to hear from New York state,” said Jonathan Mariner, who created TaxDay, an app that tracks users’ locations so they don’t overstay the threshold of days that would trigger residency status, which is typically 184.

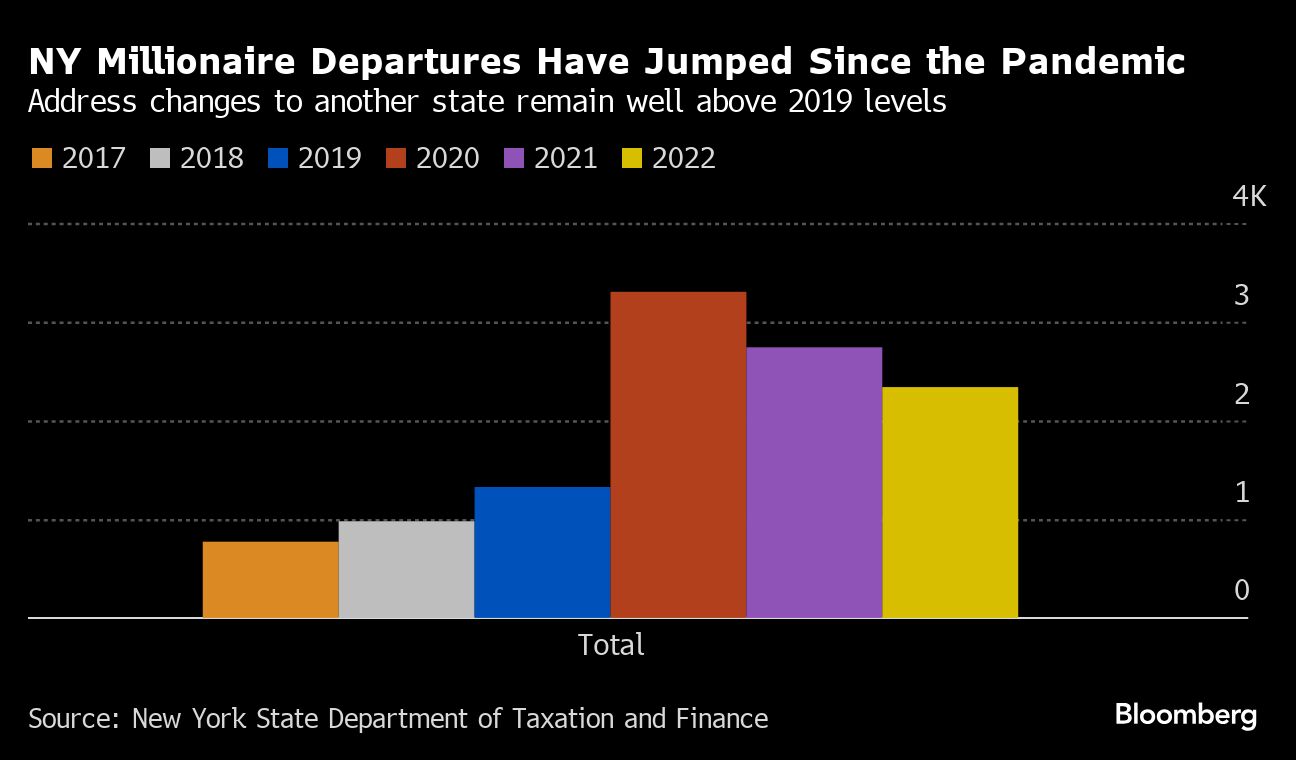

The whereabouts of the wealthy are particularly important to New York, a high-tax area where the loss of even a handful of rich residents can have an outsized effect on budget revenue. The state has been especially hard hit by departures since Covid-19 fueled the rise of remote work: The number of taxpayers earning more than $1 million who moved out more than doubled in 2020 from 2019 and has continued each year to be well above pre-pandemic levels, according to the Department of Taxation and Finance.

That’s leading state officials to try to claw back money wherever possible through residency audits — an investigation into whether someone correctly identified themselves as a full-time, part-time, or nonresident for income-tax purposes. It’s also taking place in California, another relatively high-tax, high-departure state facing budget strains, where the number of residency audits closed in the first 11 months of 2023 more than doubled from before the pandemic.

For some of these people, often accustomed to the privacy and ease afforded by wealth, a residency audit can be an uncomfortable dive into their daily life. New York’s auditors closely watch travel and apply a standard known as “the teddy bear test,” looking to see where individuals keep their most cherished possessions to determine whether a home is their primary residence.

“We always tell people the tax audit from New York is like the tax version of a colonoscopy,” said Mark Klein, a tax attorney at Hodgson Russ.

“I’ve had cases that have hinged on a single dog,” Klein said. “And I had a case once that was based on the fact that the person moved their Peloton bicycle to Florida.”

Counting Days

Residency audits have long been big business in New York. The state collected roughly $1 billion from 15,000 audits between 2013 and 2017, according to data obtained through a Freedom of Information request. While California lags behind New York in the scale and complexity of its residency audit operation, the Golden State collected $85 million in residency audit income last year through November, the largest single-year tally in at least a decade.

Both states are still recording overall growth in the number of millionaires, thanks to income and stock-market gains, but the key for tax officials is making sure they’ve genuinely left. Since the pandemic, higher-income people moved out at a faster pace than they moved in, data from both states show. While wealthy residents have long pretended to leave to dodge taxes, tax experts say Covid brought more legitimate moves as companies embraced flexible work and set up outposts in places such as Florida and Texas, which have no state individual income tax.

New York’s tax laws are notoriously tricky. Typically, someone who lives there will be considered a resident for tax purposes, paying levies on their income from all sources, even those outside of the state. But the state considers someone a resident even if they don’t live there, as long as they’ve spent more than 183 days in New York and maintain a “permanent place of abode,” which could simply be a vacation home.

A few hours spent in New York qualifies as a whole day. Getting off the highway in New York for lunch while driving from New Jersey to Connecticut can count. So can getting outpatient treatment at a New York hospital. When you can’t prove where you were on a given day, New York auditors may assume you were in the state.

“Even though you have a Florida driver’s license, Florida voting record, Florida home, it does not matter,” said Mariner, who created his app after facing his own residency audit after moving to the Sunshine State. “You could be on vacation in New York and they’ll pull you back in.”

New York’s Department of Taxation and Finance has 300 auditors dedicated to conducting residency audits, and they are notorious for their thoroughness. Bank records, phone bills and family photos are under the microscope. Auditors are backed up by sophisticated artificial intelligence-fueled tax monitoring systems that flag inconsistencies in returns.

California, which has far fewer workers traveling across state lines on a daily basis, typically employs around 30 to 35 auditors, according to Andrew LePage, spokesperson for the state’s Franchise Tax Board. He said there hasn’t been increased enforcement through the residency audit department.

Still, Chris Parker, a principal with accounting firm Moss Adams in Sacramento, said he’s noticed increased attention from state employees charged with recouping tax income from wealthy individuals who say they have left California.

In one situation, an auditor asked a client for death records of their deceased dog and the veterinarian that handled the body, he said. Another case under appeal involves a tech investor who moved to Nevada but could be liable for $6 million in taxes because of frequent visits to California to race high-performance sports cars.

“People who moved to another state are not criminals because of their move, and yet they are regularly treated like such,” said Parker, who spent over a decade working for the state’s tax department.

‘Incredibly Reliant’

Although the total number of taxpayers leaving New York and California from 2020 to 2022 was highest among low and middle-income people, the flight of the richest individuals has an especially large impact on budgets. People earning over $1 million each year made up just 1.6% of tax filers, but paid 44.5% of the state’s total personal income taxes in 2021, New York Comptroller Tom DiNapoli said in a recent report. In California, nearly half of the state’s income taxes come from the top 1% of earners.

“We are incredibly reliant on New York’s high earners for our income tax revenue,” Amanda Hiller, the state’s acting tax commissioner, told an audience of civic leaders at a panel discussion on New York’s economic future last fall, where panelists joked about the well-timed flights and tactics of those trying to dodge residency taxes. The state doesn’t know whether millionaires are leaving because of tax policy, but officials are closely studying their movements in search of an answer, Hiller said.

In the meantime, a cottage industry is rising to serve the taxpayers navigating these issues. A residency tracking app called Chrono, which uses biometric data to prove users’ whereabouts, launched in 2021. Co-founder Luke McGuinness said it stemmed from the frustration he and friends felt as “digital nomads,” a growing class of people who work remotely and travel regularly.

Another tracking system, Monaeo, automatically logs users’ locations to create detailed records of their whereabouts. It was developed more than a decade ago but has seen an enormous increase in downloads since the pandemic, said Bill Mastin, chief executive officer of Topia, which owns the app.

“I would say 60% to 70% of our user base is specifically tied to New York,” he said.

Most Read from Bloomberg

- Traders Are Cashing Out of Markets En Masse

- New York’s Rich Get Creative to Flee State Taxes. Auditors Are On to Them

- Elon Wants His Money Back

- Nigeria’s Economy, Once Africa’s Biggest, Slips to Fourth Place

- Dubai Grinds to Standstill as Flooding Hits City

©2024 Bloomberg L.P.

2024-04-19T10:53:52Z dg43tfdfdgfd